Entities may be aware that earlier this year the IFRS Interpretations Committee (IFRIC) published its final agenda decision on accounting for configuration and customisation costs in a Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) arrangement (refer to BDO’s May 2021 Accounting Alert – click here).

For entities with 30 June reporting dates, any impact of the IFRIC decision needs to be incorporated in your 30 June 2021 financial statements… so time is very much of the essence to undertake the assessment and quantify any retrospective adjustment required.

While the decision did not result in a formal amendment or revision of any specific NZ IFRS, the decision did provide clarity as to how the existing NZ IFRSs are to be applied to transactions similar to the fact pattern the IFRIC was asked to address.

The key consequence of the IFRIC decision was that certain entities that have capitalised software implementation costs in the past, may have done so incorrectly, and if so, these now need to be retrospectively corrected (i.e. the nature of the costs do not result in a recognisable asset under NZ IAS 38 Intangible Assets).

SaaS and other similar software licensing arrangements are areas of our commercial (and wider) reality that accounting standards have not necessarily kept up to date on.

As such, the required accounting treatments of these more “modern” commercial arrangements must be navigated through the existing principles, definitions, and guidance of the suite of various NZ IFRSs.

Doing so can lead to diversity in practice in terms of the accounting applied by entities – which is when the IFRIC is asked to step in and clarify or recommend amendments to accounting standards where necessary to resolve such diversity and (re)establish consistent accounting application.

The accounting treatment of software implementation services is however one area that has recently had attention, from the point of view of the suppliers (Vendors) of SaaS products in the application of NZ IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers (effective from 1 January 2019), from the perspective of identifying whether these were stand-alone performance obligations (units-of-account for revenue recognition), or should be “bundled” with the associated license, and/or other promised goods and services being provided.

So, while the recent IFRIC decision is directly focused more on the Customers’ side (i.e. can the costs be capitalised in accordance with NZ IAS 38), the decision also consequently provides additional guidance as to how Vendors should be assessing implementation activities when applying NZ IFRS 15 for the purposes of determining separate (“bundles” of) performance obligations when applying the revenue recognition requirements of NZ IFRS 15.

This Cheat Sheet is equally applicable to Tier 1 and Tier 2 Public Benefit Entities (PBEs), as the concepts contained in the IFRIC decision could equally apply to PBEs as the accounting requirements of the equivalent PBE standards are very similar to the requirements in NZ IFRS standards in this instance.

Need assistance with NZ IFRS or NZ IFRS (RDR)?

BDO IFRS Advisory is a dedicated service line available to assist entities in adopting and applying NZ IFRS or NZ IFRS (RDR). Further details are provided on the following page for your information.

What is covered in this Cheat Sheet

In order to navigate through these areas of accounting, this Cheat Sheet is broken down into the following sections:

What are “Implementation services” with respect to SaaS and other software arrangements?

The problem currently is that the different terms used by software providers and customers colloquially in practice such as “implementation”, “customisation”, “configuration”, “integration” etc.:

(i) Are not defined by NZ IFRS,

(ii) Are used interchangeably in practice and within the software industry itself, and

(iii) Are not used consistently from entity-to-entity (and sometimes even within the same entity).

So, the first (positive) thing that the IFRIC decision does is to provide (unofficial) guidance and descriptions around this very specific area.

The key point here is that a Customer needs to know on quite a technical level what the implementation services are actually doing in the background, with the focus on “is code being added or modified?”.

This is not necessarily something that will be known by the Finance team, nor potentially something that can be easily determined by reviewing invoices from the Vendor (and even in some cases, review of the contract itself).

Accordingly, getting clarity over this typically requires discussions to be had with the entity’s own in-house IT department (that would have overseen the SaaS implementation), or failing that, the Vendor themselves

Also, given the description of configuration services above, these would generally be expected to be limited in nature and scope, and accordingly, limited in time and cost. Therefore, in situations where an entity has determined that it has significant configuration services, in may be that the entity has not correctly identified:

(a) Services that are actually (more involved) customisation services, and/or

(b) Other promised goods or services that have been provided in addition to configuration

services and customisation services (such additional goods or services that have

been executed within the customer’s own IT infrastructure environment, and/or involving

purchased or leased IT hardware).

Customers of SaaS, how should you be interpreting the IFRIC decision?

The May 2021 edition of BDO’s Accounting Alert (click here) details the key aspects of the IFRIC decision.

The first question that the IFRIC decision looks at is whether the definition of an Intangible Asset is met which would facilitate costs associated with implementation services being able to be capitalised, noting that there are two criteria to be satisfied:

(i) That there is the power to obtain future economic benefits, and

(ii) That there is power to restrict others from having access to those same future economic

benefits.

It is here, particularly with respect to (ii), where entities have “gone wrong” in their previous determination that there is an Intangible Asset present to capitalise.

First assessment

The first thing to look at is whether the licensed software itself meets the definition of an Intangible asset.

If so, it is probably highly likely that any subsequent Implementation services would meet (i) and (ii) above.

Practicably this is likely to be the case if, and only if, the software in question is not off-the-shelf, or out-of-the-box software – that is, it is software that has been specifically built for a specific Customer.

However, even where this is the case, what would then need to be assessed is the rights around the intellectual property, IP, (i.e., the code) that has gone into building that software, and who has contractual rights (of use) to it.

If the Vendor retains IP rights to the software (and its code), then the Customer would typically be unable to demonstrate that (ii) has been met (i.e., the Vendor is not restricted from using the software code for the development of future software products for other potential customers).

If the IP is contractually protected for a period of time (i.e., the contract period), then it is arguable that the Customer satisfies (ii), but only for the period protected (which would then be the amortisation period of any Intangible asset recognised, unless the useful life of the software is shorter).

Assessing such IP protection would require specific analysis of the contract, as well as potential advice from legal experts regarding the legal and practical enforceability of such contractual clauses.

Second assessment

The second thing to look at is, even if the licensed software itself does not meet the definition of an Intangible asset (for the reasons above), whether the additional implementation services (most likely the customisation services) themselves meet the definition of an Intangible asset.

The analysis that needs to be done here is the same as in the First assessment above, being that an entity needs to consider and confirm whether the IP relating to the additional and/or modified code is contractual (and legally) protected, such that satisfaction of (ii) can be demonstrated.

Note that this Second assessment may still be necessary to consider even where the software itself does meet the definition of an Intangible asset (particularly if the contract is “silent” about specific aspects of the software build).

Treatment where costs are able to be capitalised as an Intangible Asset

Standard NZ IAS 38 accounting is applied, being that costs are capitalised and then amortised over the shorter of the licence period, IP protection period (if relevant), or the useful life of the software.

Treatment where costs are not able to be capitalised as an Intangible Asset

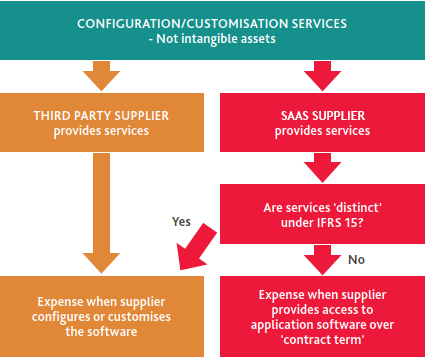

Again, this area was covered in some detail in the May 2021 edition of Accounting Alert (click here) with the below useful diagram:

The key point here is that even though there will be no Intangible Asset recognised, there may be instances where a Prepayment asset might be recognised (i.e., where amounts paid to the Vendor are in advance of the associated expense being recognised for accounting purposes).

The key difference between the three potential scenarios from the diagram above is the period over which the expense relating to the costs incurred for implementation services is spread, being:

- A shorter period (i.e., over the period that the services are provided) if the services are provided by:

- A third-party (i.e., different from the software Vendor), or

- The software Vendor, where the implementation services are “distinct” (see below)

- A longer period (i.e., over the licence “contract term”) if the services are provided by the software Vendor, where the implementation services are not “distinct”, i.e., “bundled” with the licence (see below).

It should be noted that the “contract term” itself is a matter that can be “grey” in practice, in particular where the licence is an open-ended (perpetual) licence.

Entities therefore need to consider which of the below guidance in NZ IFRS 15 is most appropriate in their particular situation:

- The period over which there are enforceable rights - were termination and renewal clause

analysis becomes critical), or

- The likely period over which the Customer will access the software, based on substance

(i.e., the use of the Customer’s unilateral rights to renew and/or terminate the licence).

Whether or not the implementation services are “distinct” requires an assessment of NZ IFRS 15 from the perspective of the software Vendor, with respect to identifying separate (“bundles” of) performance obligations.

These are explored further in section 3. below.

Vendors of SaaS, how should you be interpreting the IFRIC decision?

The guidance within the IFRIC decision makes reference to (and in doing so, provides additional application guidance, with respect to) the application of NZ IFRS 15 in terms of the Vendor-side of the transaction.

In particular, the identification and description of implementation services between configuration services and customisation services, provides clarity as to how:

(i) Implementation services (irrespective of what they may be referred to as in practice) may

need to be disaggregated and classified based on the nature of what is (or is not) happening,

with respect to adding and/or modifying the underlying code of the software, and then

(ii) How these classifications are assessed against the performance obligation separation

requirements of NZ IFRS 15 paragraph 29, to determine whether they are separate and

“distinct” performance obligations.

Separate and “distinct” performance obligations

Under NZ IFRS 15, individual promised goods or services are bundled together into a single performance obligation where:

(a) They are significantly integrated with each other, or

(b) They significantly modify or customise each other, or

(c) They are highly dependent or interrelated with each other.

The key qualitative feature to keep in mind is that in order for the above indicators to be met, there should be a transformative relationship between the individual promised goods and services in question (rather than merely a functional relationship).

Other key points for entities to remember when assessing separate “distinct” performance obligations:

Configuration services

- By their nature, as these services do not result in adding and/or modifying any of the software’s

underlying code, the relationship here is less transformative.

- It is thereof likely that these types of (less transformative) configuration services are less likely to

be “bundled” with the licenced software, and instead more likely to be considered (subject to

materiality) a separate, distinct performance obligation - i.e. separately identifiable from the

customer’s right to receive access to the vendor’s application software.

Customisation services

- By their nature, as these services do result in adding and/or modifying any of the software’s

underlying code, the relationship here is potentially more transformative.

- However, consideration still needs to be given to exactly what the customisation is resulting in,

and whether this demonstrates a (true) transformative change in HOW the software operates.

For example, customisations that simply change the background colour, font etc. are not

particularly transformative in nature.

Whereas, customisations that modify existing applications or functionality within the software,

and/or add on additional features and/or modules, are clearly more transformative in nature.

Accordingly, these clarified descriptions will now better equip Vendors of SaaS and other software licencing from determining the nature and quantum of the distinct (bundles of) performance obligations being provided

Final thoughts and your go-forward requirements

The IFRIC decision has directly resulted in questions being asked of the appropriateness of software-related Intangible assets currently recognised on the balance sheets of Customers of SaaS and other software licence arrangements.

Many of these entities are being required to undertake “deep dive”, retrospective assessments of the nature of past costs associated with implementation services that have been capitalised.

Indirectly, the IFRIC decision has refocused Vendors of SaaS and other software licence arrangements regarding the nature of their separate promised goods and services, and the make-up of their (bundles of) separate performance obligations to which revenue recognition accounting under NZ IFRS 15 is to be applied.

Accordingly, entities in either camp will need to make sure that they:

(i) Understand the nature of the IFRIC decision.

(ii) Confirm whether it is applicable to them.

(iii) If applicable, determine how the impact will need to be assessed.

(iv) Undertake the assessment.

(v) Make retrospective adjustments to financial statements for any changes in accounting

treatments required.

As noted above, it may be that engagement with an entity’s internal IT department and/or the

Vendor is required to undertake this assessment accurately.

For entities with 30 June 2021 reporting dates, the above needs to be undertaken for the preparation of your 30 June 2021 financial statements… so time is very much of the essence.

Customers and Vendors of significant SaaS and other software licence arrangements may need to engage the assistance of IFRS experts to assist with (or undertake) this assessment

BDO IFRS Advisory

Members of BDO’s IFRS Advisory department come ready with real life experience in applying IFRS and are therefore well placed to provide entities with the expertise and assistance they require.

For more information as to how BDO Accounting Advisory Services might assist with your entity in navigating this and other areas of IFRS application, please contact James Lindsay at BDO Accounting Advisory Services (james.lindsay@bdo.co.nz, ph +64 9 366 8041), and visit our webpage.

For more information as to how BDO Accounting Advisory Services might assist with your entity in navigating this and other areas of IFRS application, please contact James Lindsay at BDO Accounting Advisory Services (james.lindsay@bdo.co.nz, ph +64 9 366 8041), and visit our webpage.

For those entities still working through their adoption of the new lease accounting standard (NZ IFRS 16), visit our dedicated Adopting NZ IFRS 16 webpage for more information and resources on NZ IFRS 16.

This publication has been carefully prepared, but it has been written in general terms and should be seen as broad guidance only. The publication cannot be relied upon to cover specific situations and you should not act, or refrain from acting, upon the information contained therein without obtaining specific professional advice. Please contact your respective BDO member firm to discuss these matters in the context of your particular circumstances.